With Joel Warner (Cross posted on The Humor Code’s Psychology Today blog)

Some of civilization’s great thinkers pondered the meaning of humor long and hard. Thomas Hobbes put forth the idea that humor emerges from superiority or “sudden glory” over an enemy. Immanuel Kant believed humor arose from a process of incongruity in which a “strained expectation” is transformed into “nothing.”

Unfortunately, these theories and many others, while compelling, haven’t withstood the test of time. Superiority, for example, has trouble explaining why the victim of a tickle attack does the laughing (rather than the aggressor). Moreover, whereas incongruity theories seem to do a good job of explaining what is funny, it has trouble explaining what is not funny.

Why have humor theories long fallen short? Maybe it’s because thinkers have spent too long thinking about them, and not enough time subjecting them to empirical tests.

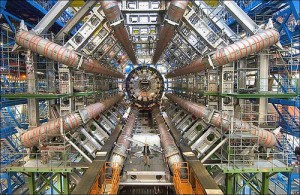

It’s easy to understand the lure of thought experiments for those trying to figure out what makes things funny. After all, to get at humor’s core building blocks, you don’t need anything as complicated as reverse transcriptase, cell cultures or a particle accelerator. You just need jokes. To test humor theories, therefore, all you need to do is come up with a lot of jokes and see if they fit, right?

Wrong. Although thought experiments are undoubtedly helpful when other forms of analysis aren’t available (Galileo famously used thought experiments to examine the effects of gravity), they have substantial limitations. Although we might like to imagine our minds as pure and unbiased analytical tools, psychological science is littered with examples of how our well-meaning intuition leads us astray. For centuries, philosophers and theologians conjectured that people are inherently good or bad. But as demonstrated by the famous Milgram experiment, in which people were willing to subject others to what they believed were painful electrical shocks because they felt compelled to follow orders from an authority figure, even “good” people can do very bad things indeed.

Here are three reasons why thought experiments will get humorologists only so far:

1) Errors of introspection. Psychologists Richard Nisbett and Tim Wilson compellingly demonstrated the difficulties people have about understanding their own cognitive processes. For example, in one experiment, they presented people an array of nylon pantyhose and asked them to choose which was the best quality, never telling the subjects that the pantyhose were actually all identical. Participants showed a strong tendency to choose the pantyhose on the far right, although none of them believed the positions of the pantyhose had anything to do with their selection.

2) False consensus. Whether you like it or not, you have a tendency to think that others will believe what you believe, value what you value and behave as you behave. The classic experiment on the matter asked people to wear a sandwich board in public that said, “Eat at Joe’s.” Those wearing the sign were then asked if they would eat at Joe’s. Those who said yes expected that a majority of people would also do so. Those who said no expected that a majority of people would to say no, too. False consensus is especially problematic in humor research, because people vary widely in what they find funny.

3) Confirmation bias. Thought experiments are often designed not to test a point, but instead prove a point. This is likely the reason why a 2001 Gallup Poll found that about 50 percent of the U.S. population believes in ESP. Since people are much more likely to remember times they correctly predicted the future than the ho-hum times they were wrong, it’s easy without careful record keeping of all predictions to come to the mistaken belief that you’re the second coming of Nostradamus. In the same way, humor researchers conducting thought experiments are likely to seek out examples that confirm their hypothesis, rather than pit competing hypotheses against each other.

Taken together, our mind’s foibles make for a very sloppy laboratory. Errors of introspection limit our ability to notice our thought processes go wrong. False consensus makes it hard to see why things that make you laugh don’t make others laugh. And confirmation bias limits the thought experiments to those that are most likely to confirm a hypothesis.

But since humor is so amorphous and subjective topic, is it really possible to tackle the subject using anything other than thought experiments? Using state-of-the-art technologies and testing procedures, researchers have been doing so for several decades, and in the process shooting full of holes a variety of humor-oriented thought experiments. Take how lay people and humor researchers alike often insist humor involves surprise, that something is only funny if it’s unexpected. But in 1974, Howard Pollio and Rodney Mers ran a laboratory study involving two groups of participants. They asked one group to listen to comedy tapes of Bill Cosby and Phyllis Dyler and rate the funniness of the punchlines. Another group heard only the comedians’ set-ups, and were asked to predict the punchline. What happened next was both counter-intuitive and fascinating. The punchlines that were rated funniest were also the ones that were most likely to be predicted by the other group. In other words, surprising punchlines were less – not more – funny.

Using jokes and other philosophical ruminations to illustrate humor theories for colorful conversations and good cocktail-party chatter. But if we really want to understand what makes things funny, we have to rely on hardcore science. Thankfully for everybody involved, a hadron collider won’t be necessary.

—————————————————-

For more about the Humor Code, check our:

Web page.

Facebook page.

Twitter account.

Wired blog.

Psychology Today blog.