Last week at Ignite Boulder, Joel Gratz (@gratzo), a famous Boulder meteorologist and creator of weather websites for winter sports enthusiasts (coloradopowderforecast.com) and summer sports enthusiasts (dontgetzapped.com), gave a talk, “Hire a Meteorologist, Not a Stock Broker.” He argued that meteorologists are more accurate than you might think (and certainly more accurate than other people you may rely on for advice, especially your stock broker).

I asked him how you can better understand your weather forecast:

Judging judgments about the weather

The many ways of interpreting the statement, “There is a 40% chance of rain,” was surprising and a bit disconcerting. To me, the a consumer’s judgment of 40% of the area for 100% of the time is a much different than 80% of the area for 50% of the time.

I also looked more deeply into Joel’s answer to second question, “What is the difference between partly cloudy and partly sunny?,” and found this on the answer on USA Today’s weather FAQ’s:

Q: What do terms such as “partly cloudy” or “mostly sunny” mean?

A: For public forecasts, the National Weather Service uses the following terms to indicate how much of the sky should be covered by clouds:

- Cloudy: 90-100%

- Mostly cloudy: 70-80%

- Partly cloudy or Partly sunny: 30-60%

- Mostly clear or Mostly sunny:10-30%

- Clear or sunny: 0-10%

In short, consumers of weather forecasts might want to follow Joel’s advice, if your meteorologist says “50% or higher,” you better pack your umbrella.

Want to learn more?

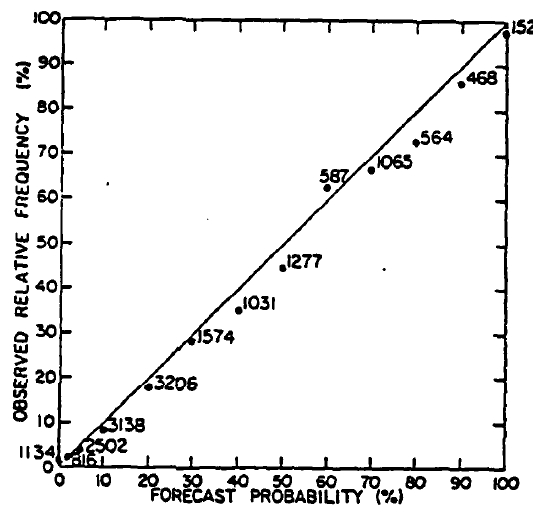

1) A famous paper by Murphy and Winkler (1974) presents the counter-intuitive finding that meteorologists are surprisingly accurate at predicting the weather. This figure says it all (Note: the numbers in the figure show the number of observations at each probability level):

Murphy, A.H. & R. L. Winkler, 1977: Can weather forecasters formulate reliable probability forecasts of precipitation and temperature? Natl. Wea. Dig., 2, 2–9.

.

2) Gerd Gigerenzer and colleagues have a fun paper that investigates how people interpret these kinds of probabilities:

The weather forecast says that there is a “30% chance of rain,” and we think we understand what it means. This quantitative statement is assumed to be unambiguous and to convey more information than does a qualitative statement like “It might rain tomorrow.” Because the forecast is expressed as a single-event probability, however, it does not specify the class of events it refers to. Therefore, even numerical probabilities can be interpreted by members of the public in multiple, mutually contradictory ways. To find out whether the same statement about rain probability evokes various interpretations,we randomly surveyed pedestrians in five metropolises located in countries that have had different degrees of exposure to probabilistic forecasts––Amsterdam, Athens, Berlin, Milan, and New York. They were asked what a “30% chance of rain tomorrow” means both in a multiple-choice and a free-response format. Only in New York did a majority of them supply the standard meteorological interpretation, namely, that when the weather conditions are like today, in 3 out of 10 cases there will be (at least a trace of) rain the next day.

Gigerenzer, G., Hertwig, R, van den Broek, E., Fasolo, B, and Katsikopoulos, K. V. (2005). A 30% chance of rain tomorrow: How does the public understand probabilistic weather forecasts? Risk Analysis, 25, 623–629.

.

3) Finally, check out Steve Dunbar’s post, featuring a DIY study by J.D. Eggleston,: How valid are T.V. weather forecasts?

The results were quite enlightening, as were some of the comments of the local meteorologists and their station managers. Here a few of the quotes we received:

“We have no idea what’s going to happen [in the weather] beyond three days out.”

“There’s not an evaluation of accuracy in hiring meteorologists. Presentation takes precedence over accuracy.”

“All that viewers care about is the next day. Accuracy is not a big deal to viewers.”

The weather forecast says that there is a “30% chance of rain,” and we think we understand what it means. This quantitative statement is assumed to be unambiguous and to convey more information than does a qualitative statement like “It might rain tomorrow.” Because the forecast is expressed as a single-event probability, however, it does not specify the class of events it refers to. Therefore, even numerical probabilities can be interpreted by members of the public in multiple, mutually contradictory ways. To find out whether the same statement about rain probability evokes various interpretations,we randomly surveyed pedestrians in five metropolises located in countries that have had different degrees of exposure to probabilistic forecasts––Amsterdam, Athens, Berlin, Milan, and New York. They were asked what a “30% chance of rain tomorrow” means both in a multiple-choice and a free-response format. Only in New York did a majority of them supply the standard meteorological interpretation, namely, that when the weather conditions are like today, in 3 out of 10 cases there will be (at least a trace of) rain the next day.