Compared to research on married people, there is little being done to investigate the well-being of single people. Fortunately, Geoff MacDonald, a social psychologist at the University of Toronto has turned his attention to examining singlehood. Peter McGraw is joined by guest co-host Iris Schneider to discuss Geoff’s recent academic paper that investigates predictors of life satisfaction for singles. The conversation will help you understand why you are coping or thriving as a single person.

—

Listen to Episode #160 here

Are You Thriving Or Coping?

Compared to research on married people, there isn’t enough being done to investigate the well-being of single people. Fortunately, Geoff MacDonald, a social psychologist at the University of Toronto has turned his attention to examining singlehood. Geoff is joined by returned guest co-host Iris Schneider, a professor of Social Psychology at the Technical University Dresden. Iris studies mixed feelings and conflict in judgment and choice. We discussed Geoff’s published paper that examines predictors of life satisfaction for singles. I hope you enjoy the episode. Let’s get started.

—

Welcome back, Geoff.

Thanks for having me.

Welcome back, Iris.

Thank you. I’m glad to be here.

We’ve talked about attachment style, its usefulness and the problems associated with the theory. The three of us are back to talk about thriving as singles or as I would say, to talk about singles living a remarkable life. We’re here specifically to talk about a publication of Geoff. What is the title of this publication?

Coping or thriving within a person’s perspective on singlehood, which is not exactly the title. Yuthika Girme is the first author of this. Yoobin Park is the second author. It’s a big team effort. It focuses on within-group perspectives on singlehood.

For readers, who want to stop reading, I swear it’s going to be interesting. Don’t let that title scare you off. Singles are often excluded from research on well-being. When I say excluded, they’re not looked at. They may be part of the samples and so on but the specifics of thriving as a single is not something that you find in the well-being literature.

This is my comment that too much of that literature is a one-size-fits-all perspective. “This is how you live a good life,” and there’s a small number of ways you’re supposed to live a good life. My argument is there’s not just one remarkable life. There are remarkable lives whether you’re partnered, single, within a group of partnered people or a group of single people. Let’s start with a very fundamental question, Geoff. Why was it important for you to do this inquiry or write this paper?

Single people have gotten short shrift in terms of attention when it comes to happiness and well-being research. In general, the field and our lab have been paying more attention to single people. Essentially, we were asking the question, “Which single people are happy? Which single people are less happy?” We felt like that was particularly important because a lot of the research that had been conducted on single people was focused on comparing single people to people in relationships.

I do think that that reflects exactly the societal biases that you’re talking about, where the assumption is that people in relationships are healthy and you need some contrast against them. What you ended up with then was not a lot of information about the variety of different types of single people that are out there. The literature was suggesting that on average, people who were in relationships were higher in well-being than single people but it didn’t distinguish what kinds of single people are you talking about.

The more that people poke into this research, there are a lot of different types of single people out there. Some of whom are thriving and some of whom are not doing so well. That’s where the thriving versus coping part of the title came from. We wanted to focus on single people and what distinguishes the happy single people from the less happy single people to see if we could come up with at least an initial take on, “Whom would you expect as a single person to be living a life that they’re enjoying and who’s not going to be doing so well?”

It’s important to say that it’s already ambitious to look at single people as a whole because that includes eighteen-year-old college kids, middle-aged empty nesters, widows and divorced people. The last time I checked, the oldest person in the world is a 108-year-old woman. That’s already a big swath of society but I commend you for even focusing on that swath and one that reads this.

We think it’s important to work. We enjoy doing it. For the record, when you get to 108, you’re almost certainly single. This is especially important for her.

It’s my hope. In your wonky title there, you say within the group.

Focusing on single people, that’s what that means.

Why is it so important to do this within-group endeavor?

The argument has been set up to show that people in relationships are doing better than single people. It ignores the possibility that even if you do take it as the average person in a relationship is happier, there are going to be so many people even within the single group that is doing great. Largely, what we were trying to do was to shine a light on that to make the point that there are particular conditions under which single people are likely to be doing well for themselves. By setting up the review this way, we could shine a light on who are the people and what are those conditions lead to people doing better.

This harkens back to the second episode of the show in which I had Bella DePaulo on. She makes a very convincing case that when you look at the group level partnered people tend to be more satisfied with their life on average than non-partnered people, that is not a causal relationship. What ends up happening is people will interpret it or even worse prescribe partnership as a way to become happier. If someone is sitting here who is unhappy and thinks, “If I get partnered, I can become part of the happy group,” it doesn’t seem to work that way.

To give away one of the punchlines of the paper is that the people who were happy being single to a large extent are the same kinds of people who are happy in relationships. One of the things that I’m fond of saying is that it suggests that getting right with yourself first, regardless of whether you’re someone who wants to be single or to be in a relationship is probably going to be the better route to happiness than looking for somebody else to make you happy in whatever form you do that.

When I read the paper, it was such an admirable work. It’s wonderful also the way it’s set up looking at interpersonal so experiences of the person themselves, experiences with other people and then in society as a whole. As I’m digesting the paper over a few days, I got the sense that this paper says, “Humans are happy when they have good relationships and their needs are met.” They are not when they’re not. Maybe one of the biggest things that your paper says is that single people are also humans. They need friends and not to be rejected.

We are not monsters.

We’ve been brought into the realm of human behavioral science as worthy of study. I wonder what the implications are because what you’re saying also with this paper is that relationship status is maybe not the most important thing to predict well-being from. Are you in a way undermining your whole endeavor as a relationship researcher with this paper by saying, “Partnership doesn’t matter. It’s all about other factors that make us humans?” I like that because I was thinking, “How did this historically get started to look at relationship status as the main predictor for different outcomes?” Why did this become the IV, to begin with?

It’s an interesting perspective. I agree with you. Everybody to be happy needs to have their needs met. One of the fundamental assumptions has been that having a partner is a need for everybody That’s one of the central things that we’re trying to unpack in all of this is the assumption that everybody has the need for a partner. There’s a lot of variability in that, a lot more than researchers have paid attention to.

From my perspective, one of the things I try to keep an eye on is that at least for the time being, it’s more often that people do want to partner than don’t. That’s why it ends up looking like being in a relationship is good for well-being because the majority of people want that but that doesn’t mean that people who don’t want a partner are then going to magically be happy when they get one. For whatever reason, we lived in a society where it shifted, where the majority of people did not want a partner, then having a partner would probably negatively predict people being happy. It’s still the case that it’s normative. That’s that. We then can unpack why it’s normative.

Give us another 50 years. Iris and I are working on this. In 50 years, they’re going to need a show called Partnered, The Partnered Person’s Guide to a Remarkable Life. They’re going to be complaining about how all the single people in the world treat them badly.

Some of my best friends are partnered.

It’s true. I have partnered with friends. There’s nothing wrong with them. These married people are a little weird but they’re living their life. I’m not going to judge them for it.

You do you.

With 18-year-old college kids and the 108-year-old oldest person in the world, if you partnered that person up, are they going to be happier? I’m not so sure. It shows where you are in your life and what your goals are. Geoff, I want to echo something that Iris pointed out in terms of the broad scope that you were looking at.

In well-being research, there’s a dependent measure or an outcome. Often, it’s satisfaction. On balance, “How satisfied are you with your life?” That’s the typical one. There are different versions of that. I want you to talk about that. There are predictors or independent variables. “What is it that predicts whether it be you’re high or low on this?” The nice thing about science and statistics is that we can pull out the individual effects like controlling for other things. How much do connections to others matter? How much does wealth matter? For those independent measures, factors and predictors, you have three general classes. Can you talk about each one of those and why you selected them?

In general, the reason that we went about that is there’s an established field of well-being research and they have particular ways that they look at things. This is one framework that these kinds of researchers have used before. One of them was intrapersonal. This is the person you are or the characteristics that you have as an individual. That came partly from the stuff that I’ve done before on attachment, the idea that some people are more versus less secure and that might affect how motivated they are to be close to people in relationships.

The second is interpersonal, which is the social experiences that people have. For example, one thing that might make you more or less motivated to be in a relationship is what relationships are out there. Are there attractive people out there? Are there sexual opportunities out there? Are people generally jerks? That would affect whether you want to be close to people or not.

The other one is societal so that’s a social attitude, stigma, discrimination and the social environment that people exist in. All of those have the potential and not necessarily in the same directions and the same ways to affect people’s choices. One of the things that I’ve found interesting about this research because you mentioned the dependent variable side is, “What are you trying to predict?” One of the things we’ve been finding there is that we tend to focus on a couple of things. One is, “Are you happy with your life overall?” The other one is, “Are you enjoying being single?”

That’s not the same question necessarily. We have found some things that are related to people being happier being single that isn’t necessarily related to their happiness overall. We think that there are probably going to be some cases where things that make you happy about being single might make your life worse like there are things about being in a relationship that you like about the relationship that causes you to conflict at work or in other parts of your life.

That’s one of the things we’ve been enjoying. It’s complicated. Both are the things that are affecting you on the independent variable side. Here’s what’s coming from inside you. There are messages that you’re getting from society and those don’t always go in the same direction but even the thing that you’re trying to predict is, “Do you want to know if you’re happy being single? Do you want to know if you’re happy with your life overall?” There’s a lot to unpack in all of it.

For those readers to who’s these terms and ideas are new, there’s the intrapersonal factor. These are the characteristics of the individual, what they think, what they feel, what their goals are and what’s going on inside. There’s the interpersonal factor. This is our connections to others and the experiences that we’re having. There’s this societal influence. What is the culture that we’re part of? What is the environment that we’re in?

You’re predicting either happiness with being single or happiness with your life, in general. Before we get into those specific findings, can you give us a glimpse into how happiness being single and happiness with your life aren’t a one-to-one mapping? Where are those points of tension? Where have those things diverged?

One of the things that have been coming through fairly consistently in why people like being single is you get a lot of independence, freedom and autonomy. By definition, the more that you’re independent of other people, the more challenging it is to socially connect with people. You can set up ways to meet both of those needs at the same time but there’s an inherent tension between the two of them.

I’ll talk about the avoidantly attached people the people who like more distance and like to be more self-reliant, that one of the reasons they might like to be single is that people can be a real hassle sometimes. You avoid the hassle of other people but then after a couple of days of being by yourself and avoiding hassles, you might start to get lonely. We think that that might be the case. You enjoy being single because of the freedom but sometimes the loneliness gets you and not necessarily overall as happy as you could be.

I have a lay theory about this. I like autonomy, independence and being by myself but I also like people who are like me. What happens is sometimes I find somebody romantically interesting and they are like me. They’re independent, like their autonomy and don’t need to be around people all the time so it never works out. You’re like, “You’re cool,” and then five days, nothing. This is for me. This is the conundrum. Like begets like or similarity attraction. If ever I do find somebody interesting, it’s never going to work out because neither is motivated enough to get something going. It has led to many great acquaintances but not anything else.

The ships passed in the night. There’s another version of this, which is that you enjoy your freedom, autonomy and independence. You meet someone and connect with them but they’re looking for something traditional. They want to spend all their time with you. Now, you’re repulsed by them. You’re like, “Slow down. Give me some space.” You’re a little bit in the catch-22.

I like it here. It’s an interesting space.

If I can make a little PSA for this idea that I call relationship design as a potential solution. This is something that Geoff has keenly interested in societal influences. It’s very difficult to think about relationships without thinking about the 800-pound gorilla of relationships. That is the relationship escalator, a traditional long-term relationship and all the rules associated with it. That gorilla is so big and powerful that it influences the way people do well-being research. It influences their assumption that people are going to be better off being connected. That’s what Geoff’s research is battling.

This is built off of relationship anarchy. There’s a Relationship Anarchy episode that is worth checking out. The people in the relationship, whether it’s romantic, familial, friends or professional but let’s talk about romantically for a moment, decide on the rules and expectations of the relationship. They have regular conversations about how’s it going, what is it that I want and what is it that you want.

A few years ago, I met a woman and we started seeing each other. Let’s say it was a budding romantic relationship. She said to me very apologetically one night, “I’m launching a product. I’m not going to be available very much for the next couple of weeks.” She was saying to me, “We’re not going to be able to see each other so maybe we should stop this.”

From an escalator standpoint, that made sense. I said to her, “I want you to be successful in launching this product. I’m not going to ask for any of your time but if we take a design approach, we can agree that as long as we both agree to not even communicate for six weeks or maybe text or maybe have one date and as long as we’re both okay with that, then after the product launch, we can resume seeing each other somewhat more frequently.”

You should have seen her face. She had this “oh” reaction to it because she was defaulting into, “We’ve been seeing each other twice a week. We need to keep doing that for this to be successful.” I said, “If we agree, we can go two months without even talking and it’s not going to diminish our connection in some sense.” Maybe Iris, when you find that fellow autonomous, independent and freedom-loving person, a little design could go a long way.

This is such an interesting remark because I also enjoy dating from time to time. It’s like visiting a museum because it’s a person with new experiences and a life that you know nothing about, especially when there was a lockdown. I thought, “This is so interesting.” It’s like a museum sample of all these insights, stories and experiences so I enjoy it.

You call this the 800-pound gorilla or this linear life path that we talked about on another episode. I meet people who are like me but they still seem to expect that they will at some point start on this linear life path like you meet somebody who travels 50% of the time, they’re not at home, being contrarian, they want to be by themselves but they still envision some settling down or something down the road. I’m thinking, “I don’t think that’s you but maybe you need some more time to figure it out.”

They think they are looking for a traditional thing, even though they are not at all in a position to offer that to somebody. You’re right that it’s so strong that people always seem to see that even though it doesn’t seem to fit their personality at all. It’s funny. I’ll think about this relationship design. I like this.

This is one of the biggest conclusions I’ve come to and putting my head into the singlehood space where everything is on the table in terms of how you design your life. This is why I emphasize that part about getting right with yourself before you start making choices about relationships or not. You need to design your life around who you are and what you want.

I’ve come to the conclusion that there are people whose best life is not going to be 10 out of 10 on life satisfaction. Certain people have this internal contradiction. Maybe you’re the person who likes alone time so much that you’re going to need to structure some loneliness into your life and that’s the best life for you. That’s one thing I’ve tried to do in all of this. Sometimes we confuse a happy life with a valid life. There are lots of valid lives that are not 10 out of 10 in terms of satisfaction in some particular domain. You need to figure out where’s your best point, balance and all of these different things. Being alone this much makes me lonely sometimes but all up, that’s the best life for me.

A couple of quick notes before we get into some of the specific results. I like Henry Rollins. He’s one of my idols when it comes to solo living. He said, “I’m a dog but not the kind you pet.” He very much will push away potential relationships because they impinge on his creation process. He’s a machine. He’s constantly turning out ideas, writing, books and going on these solo adventures. He’s been to North Korea and Afghanistan alone. A partner would not be happy with him doing that. He very authentically knows that he is better as a solo in this way. I don’t see him changing to Iris’s point anytime soon.

Our founding fathers in America made a little bit of a mistake when they talked about the pursuit of happiness. I wish they had said the pursuit of a good life. The idea being is that a happy life has a particular meaning, at least in our world, which is a life of pleasure or positive emotions but a good life is a life that you want to be living. It may have rather scarce pleasure in it because you’re building a business, you’re an artist or doing challenging things and you don’t have much leisure and a lot of ease in your life.

If you took away that creation process, that meaning, the building or whatever it is and gave the person more pleasure, their life would be less good, even though it was technically happier. Scholars are starting to figure this out and then hopefully regular everyday people were recognized how happy you are and how much joy you have can be good but might be getting in the way of these other endeavors.

I like your comment so much, Geoff. You have to get right with yourself. What does that mean to get right with yourself? I’m around a lot of young people and they often want advice on what major or career they should pick. Should they go on to be a therapist or researcher? I don’t know if it lands at all but it might be the first time they hear it and maybe they need to hear it 100 times more or maybe they need to turn 35 before they get it as I did. In the end, it’s about understanding what your values are and making a life that fits those values.

If your values are good close relationships, security or something like this, then you need to create a life around that. For instance, Henry Rollins has autonomy, adventure or creation as a value. He’s living a life that caters to that and that gives meaning. When there’s a fit between your life and your values, then you feel like you have a good and meaningful life.

Society as a whole also tries to instill values in people, either through the government with incentives for certain types of lives and acceptance of certain types of lifestyles or orientations. I would say marketing as well. You try to instill certain values that make people buy your products per se. It’s hard to make sense of.

Looking at what is traditional, what is the majority doing and what is prescriptive in a way puts some people on the wrong path. They have values that are not their own or they try and live a life that’s not authentic to who they are and that can be very confusing. It’s difficult to find out what is important to you and what are you willing to sacrifice for that.

It’s especially difficult when people marry young. That’s very well said. Let’s talk about some of the key results of this project, Geoff. Can you give people a little bit of background about the sample and how you did this? After you do that, introduce some of the findings that you’ve had.

What we tried to do was review every paper on singlehood and well-being that we could get our hands on. There are not that many papers. We felt like we ended up doing a decently comprehensive job because it’s such a young field. It’s such new research. I feel like everything’s provisional and up for debate. There are lots of types of single people that haven’t had a lot of voice in the debate yet.

I like to throw stuff out there but nothing is definitive that we’re going to talk about. That’s what makes this so much fun. There’s so much to learn about it but we tried to scare up all of the research on singlehood that we could. We tried to focus on papers that could give us samples of single people that we can focus on. We can go through some of the highlights here. A lot of it is not shocking.

I’m glad you’ve pointed this out because everybody wants to be surprised. “There are these counterintuitive findings,” but good science should match your intuitions as a smart experienced scientist or the experiences of regular everyday people. The fact is when I was reading through these results, I thought they were interesting but I wasn’t gasping.

I appreciate you saying that.

Maybe they’re not shocking to us. What is shocking maybe is that nothing is shocking there. When you look at traditional research, it’s always like, “Single people are super unhappy. They cry in their bed all the time. They have lower well-being. They’ll die young because they’re alone in the woods and nobody will find them. They’ll be forgotten.”

I didn’t mean to make a comment on triviality when I said, “This paper shows that single people are humans with normal human needs that can be satisfied in different types of ways.” For people outside this space who don’t think about relationship research or singlehood all that much, maybe it might be shocking because it’s such a common implicit belief that being partnered or being married is good and being alone is bad.

Everybody’s like, “Let’s get to the results,” but I need to editorialize. Thanks to you, Iris. I wrote up an op-ed and it’s under review. I’ll end up sharing it with the community and you can sign up for it at PeterMcGraw.org/SOLO. It was in response to four articles that came out within a month in the New York Times, Washington Post and Financial Times, all lamenting people living alone and people spending time alone.

Iris, to your point, all of these articles were like, “Doomsday. Prepare for the loneliness epidemic. This is terrible, ” and all these bad things. As you might imagine, the response to these that I’m writing is the value of solitude for some people. The idea is that some people need more solitude, not just some people need less and what is solitude valuable for and so on. This is something that Geoff is keenly interested in. As we read these things, they’re not shocking because we know that people have different goals and some people thrive when they’re alone. There’s a whole bunch of partnered people who could stand to have a little bit more alone time.

The shocking part is that there are happy single people. Once you accept that as a premise, the things that lead single people to be happy are not that surprising because as Iris astutely pointed out, single people are human beings. Before we get to the results, I appreciate you picking that up because, in our lab, psychology has gotten itself in trouble by trying to be too fancy and trying to produce these counterintuitive results that turn out the reason that they’re counterintuitive is not true. We’ve tried to do meat and potatoes or basic research to describe what’s going on in people’s lives and not position ourselves as smarter than everybody else. That reflects the values of what we’re trying to do in this research.

A lot of this stuff that we’re finding makes a lot of sense. For example, single people who have better relationships with their friends tend to be happier. They tend to be happier being single specifically. In the data that we see, having good relationships with your friends isn’t related to wanting a partner less. That’s interesting. We could go into that. Having good relationships with family is related to more life satisfaction for single people, not related to satisfaction with singlehood.

We think that that might have something to do with the tension that can come from a family where they’re emotional support but they are probably the people putting those societal values of wanting you to be married on you. Those can be tense relationships sometimes. People who are more sexually satisfied are happier being single but interestingly, more sexually satisfied singles are more likely to end up in a romantic relationship down the line.

Sexually satisfied singles are people who are having good sex, frequent sex or frequently good sex.

Our data suggest that there are a couple of different types of sexually satisfied singles. One of them is the people that you described and to put it precisely, these are the people who want to be having sex with other people and are relatively frequently having sex with other people but there is another group, which is the group of people who don’t want to be having sex.

What about people who have great sex but not with other people?

As in by themselves?

Yes. I’m thinking about some problems that come with female sexuality where sometimes the sexual experience is better by yourself.

We measured how frequently are you having sex by yourself. We tested all of these same variables I see with solo sexuality and none of it was predictive of sexual satisfaction. It wasn’t negatively predicted. It wasn’t like people who are masturbating more are less happy with their sex lives or anything. It’s just that it didn’t seem to predict. The real predictive power came from whether people are having sex with other people.

The people who are high on that are not feeling as motivated to partner up because they don’t need to solve this problem with a regular partner.

We don’t know for sure why they said that. All we know is that the people who are having more sex are less interested in having a partner. The thing is most partnered sex as things stand happen in committed relationships. In a sense, it’s one of the biggest draws for people to get into committed relationships. If you’re getting that itch scratched and you don’t need to be in a relationship to get it, then it makes sense that there’s one less draw to relationships. It’s possible that’s why but we’ve also speculated that at least a decent percentage of the people who are single and sexually active might be on their way to being in a relationship.

I’ve talked with somebody about this also. I don’t want to speak for all women but I can imagine that for women to have sex outside a committed relationship is very tricky to reign because women are less likely to switch sexual partners because of safety concerns. Once you find somebody you can have good sexual experiences with, they’re trustworthy and you are comfortable with them knowing where you live, then you would want to set up some buddy system, which is difficult because it comes so close to a committed romantic relationship.

Single women might have sex with a regular partner that is not their romantic partner but still needs a level of commitment and trust because of the intimacy of the encounters. I can see how this would easily slide. Maybe for women to have their sexual needs met, a committed relationship is safer than trying to pick up people in bars, for instance, as the other example.

Geoff’s point about the hypothesis is that some of these people are on the escalator. Iris, do they have this term in Europe called catching feelings?

Yes.

For a lot of people, sex is a very intimate thing. It also propels you to spend more time with someone, get to know them and so on. Suddenly, you start to develop these romantic bonds that you might not have otherwise.

This is especially difficult for women because the times that I’ve had such encounters, I always need a day to come down from it and put it back in perspective.

Especially if the sex is good.

The post-high is like, “He’s amazing,” but then the next day you’re like, “He’s amazing at some things,” but maybe not others.

He’s amazing in the sheets and not on the streets.

I hear what you’re saying about safety and trust. All of that is going to be encountered. I’ve also seen data and this will probably come as no shock that women find sexual encounters with people after multiple occasions to be more satisfying. Women are more likely to have orgasms with partners that they’ve had sex with multiple times than someone they’re having sex with for the first time, which is not usually true for men.

It changes the landscape of casual sex in terms of what pleasure can you expect to get out of it. In our lab, we do think about this catching feelings part of it too. There’s a paper that we name check in our paper here that I did with my former student, Samantha Jewel, where we formalized catching feelings by calling it the progression bias. We’re trying to document this idea that when you start spending time with people, those relationships are sticky. People start relationships thinking that it’s like buying a phone where if you don’t like it, you will easily take it back to the store but our feelings for people don’t quite work that way.

We make an argument that there might be a bit of an evolutionary motive behind this. Part of it is the culture thing. You’re supposed to be in a relationship and start feeling this for somebody and then you’re like, “I’m supposed to be in a relationship with them.” Think about where our ancestors came from where maybe there are ten people around you whom you could be in a relationship with. Maybe the people who started catching feelings quickly were more likely to partner up and have babies and pass their genes down generations.

The selective people who didn’t catch feelings like if you’re swiping left, waiting for your perfect partner to come along in a ten-person village, you may never reproduce. We think that it may be not necessarily surprising. It may be hard to avoid catching those kinds of feelings for people because the people didn’t get selected.

You explained my life. It takes three months for me to catch my feelings and that is way too long for the average person.

You also explained my life because I’m always running out of people. I select in a 1-kilometer radius. “That’s everybody.”

“I’ll wait for it to get repopulated.” Thank you for stopping by that one. Can you continue with some of these key findings?

That one is one of my favorites so I’m happy to stop there. One of the biggest predictors of whether people are happy being single or not is how much they desire a partner. If you have a low desire for a partner, you tend to be happier being single. This goes back to what we were talking about before. It never occurred to relationship psychologists in particular that this was a variable. People thought that this was a constant, that everybody wanted a partner.

The people who don’t are happier. The people who have never been married are happier singles. The people who have never been on a date in their life are happier singles. This goes back to trusting people to know what’s good for them. The people who’ve never been married or the people who’ve never been on a date in a decent percentage of cases are people who do that because they’re listening to their inner monologue and are like, “No, that’s not what I want.”

I love the comment, “The people who have never been on a date are happier.” I hope some people pick this up and then give advice to each other like, “You shouldn’t date because that will make you unhappy. I read this on a show. It’s science.”

One of the overarching themes in anything I’ve ever studied as a behavioral scientist, whether it be single living, humor or emotional experiences, is that there’s an objective world out there. There’s what’s happening and there’s a subjective world. That is how we perceive the world and how we value it. As a result, things that might seem objectively good might be bad. Some things that seem objectively bad might be good.

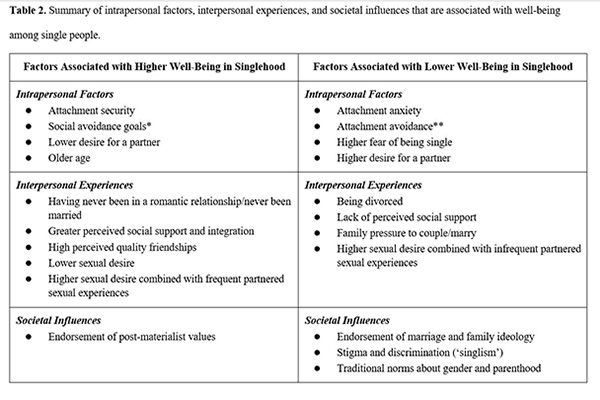

Two people may see the same thing, hear the same joke or whatever it is and one person laughing and another person offended that almost all of these effects are mediated by what people want or what their goals are. That stands out. I’m going to take an image of this table. When you read through this, it’s a lot of like, “I see that,” but so much of this is about desire, wanting and experience, where the very same outcome is either good or not good depending on the person rather than the group.

It is one of the things that come out of this review. It is true and we’ve said this already. On average, people in relationships are happier than single people but an even better predictor of that is how happy are you with your relationship status. If you’re happy with being single, you’re going to be a happier person than the person who’s unhappy about being in a relationship.

This is under societal influences. The factors associated with higher well-being in singlehood are an endorsement of post-materialist values. This is the sexiest finding in here for me because I live in a world where I say there are singles and there are solos. What I say is that solos see themselves as the whole person. They have this autonomy that Iris was referring to for herself and they tend to be unconventional thinkers. Not just unconventional thinkers with regard to relationships but unconventional thinkers more generally. The idea being if you’re willing to question whether an escalator is right for you or not, it likely means that you’re questioning whether a lot of things that are taken as commonly accepted are right for you. Seeing this in data turns me on.

I wanted to add that some of my partnered friends see themselves as solos. That gives an illustration of the independence of the two things or at least not completely independent because there’s an overlap. There are people who very much identify with this idea of shaping your life and living according to your values and not per se what is prescribed. They also read this show for that reason.

Europeans are better at being solo than Americans. I feel very comfortable saying that.

I feel comfortable hearing that. Thank you.

I do think that the post-materialist values thing is also reflective of the broader trends in society. One of the reasons that for me this is an interesting topic is that there’s an increasing number of people living alone and living without romantic partners. That’s because of these broader societal shifts where things like autonomy and independence are starting to be more valued.

Another paper had come out from my lab that is on point here. I had a student who was interested in music lyrics and was coding these music lyrics for attachment themes, including, “How much is the lyrics of these songs expressing independence, autonomy and the desire to be separate?” This is Raven Alaei, who finished his PhD and is now a medical doctor. Anytime I’m feeling too good about myself, I remember that Raven exists. What he did is he took the billboard top songs from the 1950s until the present day and tracked, “Are the lyrical themes changing over time?”

What he found is that over time, popular songs are expressing more of this independence and autonomy. It’s one bellwether of what’s going on in society, in general, where society’s values are shifting. The reason I bring that up is I find this idea that solos are these unconventional people. The one thing that I find myself wanting to put the asterisks next to that is for the time being. You talked about it as a joke but not as a joke that there may come a time when it’s not inconceivable that people in monogamous relationships could someday be the minority. At this point, they might be unconventional thinkers because they’re the ones who are going against societal trends.

For people who aren’t unfamiliar with this term, can you define what post-materialist values means?

That was Yuthika’s part of the paper. It is this shift in values towards the more autonomous or independent perspective.

There are a bunch of things that fall under this rubric. I found that to be affirming of some of the things that I’ve been observing and trying to put into my own word. Is there one last thing that you want to highlight from the findings before we move on?

The one that we haven’t talked about yet that I find interesting is age. We’ve done some work in our lab and a couple of other labs about how happy you are with singlehood. The relationship between singlehood and your happiness depends on how old you are. Relatively young people tend to be less happy with singlehood but it makes sense in the sense that if you take as a given that there’s going to be a certain percentage of people who want to be in a relationship and a certain percentage you don’t.

Among younger people, there are going to be a lot of people who want one and haven’t found one yet. Whereas once you get to about 40, there’s this inflection point at midlife where you start seeing people’s satisfaction with singlehood start to go up. It looks like older people tend to be happier with singlehood.

There was another line of research by Janina Bühler who did the same thing with people’s satisfaction with being in a relationship. You see the same pattern where people who are in relationships after about age 40, their satisfaction with the relationship starts to go up. It’s like there’s something that happens after midlife whether people are single or in a relationship where they start getting happier about that situation.

We don’t know exactly why. There’s a lot of speculation on our part as to why that might be but it’s a combination of roughly midlife, you’ve filtered yourself into the stream that you want to be in. The people who haven’t filtered themselves into the stream want to be in and figure out how to make peace with the place that they’re in. The people who wanted a relationship and didn’t end up getting one end up finding other things in their life that they enjoy and find a way to make their life good.

People in relationships do the same thing. Not everybody ends up in their ideal relationship but it’s not an unhealthy thing to be like, “How can I make the best out of this?” There’s often this sense of older people and older singles, in particular, being lonely and there’s the spinster stereotype and all of that. Our data suggest that older singles are doing better than younger singles.

One of these things that matter is as long as you’re not isolated. Some older adults are lonely and suffer profoundly but they are in a unique situation and that is their spouse has passed and they have no friends. Their friends have died or they only had their spouse and then their spouse is gone and now they’re highly isolated.

That small group is deserving of our attention, concern, interventions and so on but to these articles that I was talking about, let’s not throw the baby out with the bathwater because there are plenty of older adults who have thriving relationships involving the community, connected to family, hobbies, interests and work and aren’t feeling lacking as your data show.

We have one study that will be coming out very soon that says that the happiest singles are older women who are not interested in having a partner.

You, Iris, in twenty years.

You specifically are the happiest single person in the world. I can play this validation game too.

A couple of years ago, my dad sent me a birthday card and it said, “Keep in mind that the first 40 years can be a bit difficult.” It showed a baby. People select themselves and make the most out of what they have but also think back on episodes we did before where we talked about what it means to be an adult. For me, many people don’t grow up into their complete selves until maybe their late 30s. You start to understand what you want and need and start to feel comfortable pursuing these things as well. It also sounds like an effect of maybe maturing.

There’s no substitute for experience. You were talking about before, Iris, one of the fun things about working in a university is you’re working around so many young people. They have so much energy and excitement but I always tell them I have a mature theory, which is that you spend your twenties operating in the world in the way that you think things are supposed to work. You then get disabused of all of your assumptions somewhere around age 30 when the divorce hits or whatever else happens. You spend your 30s figuring out what it is that you want in the way that the world works. In your 40s, you start implementing that and life is pretty good.

Let’s turn our attention to the last bit that I want to do, which is the so what of all this. This is a little bit of a wonky conversation. We’re nerds and the people reading are smart but they don’t care about t-tests, ANOVAs and regression analyses. Let’s do the following if you’re comfortable, maybe each of us could share some implications of these findings for people who want to live a remarkable life, whether they’re single or may not remain single.

I’m comfortable with giving out advice.

Geoff is the most reticent. Iris and I feel very comfortable with some prescriptions here.

If you have goals and needs that are not met, you’re going to be unhappy as a single person. I would say as any human but for this paper or this topic, as a single person. One important thing is to know what you want and need and how you can get it. People might be unhappy with their lives but they don’t know exactly what it is that they’re missing. Having a conversation with yourself about what it is that you want in your life, what you value, what you need and how you can go and pursue that is generally good advice.

This puts the data under that in terms of single people who don’t want to be single. If you’re unhappy being single because you want a partner, then that is your goal and you should pursue that. A thing that we haven’t talked about it a lot and there’s no advice for that is the societal pressure on some of the singles. That is difficult but in general, the intra and interpersonal sections of this paper would say, “Understand your needs and how you can have them met.”

I want to add something to yours, Iris. It is goals work. You set a goal and it’s a good way to accomplish things but psychologically and emotionally, there are some challenges. The moment you create a goal is to live unhappy until that goal is accomplished. The case against goals is a case for the process. It’s about letting go of goals and living a day-to-day life, an hour-to-hour life or a moment-to-moment life that is rewarding. Being open to the possibilities like wanting to write a New York Times bestseller is a goal and then writing and exploring a topic is a process.

It may result in a New York Times bestseller or it may not and it probably won’t. I’m speaking about myself if that’s not obvious. Those processes may be relationship-oriented so rather than finding your Mr. Darcy is about engaging with interesting people in your 1-kilometer neighborhood whom you might be attracted to. That’s the first reaction to it. The second one is also connected to what you said, Iris, about the pressure of society.

I’m heartened to hear that love songs or pop songs are becoming more independent-focused than they were in the ’50s like Love Me Do and so on. Counteracting societal forces are very difficult because they’re so pervasive. They’re on Instagram when you open it up. They’re in the movies and the songs you listen to and the books that you read and in the conversations at dinner parties. How do you do that? One way is to create your little society or community.

There are two findings that you have, Geoff. One is that having higher perceived quality friendships is important to have higher well-being in singlehood. “My friends are supportive of my decisions. They celebrate or encourage my decisions. I can feel comfortable in the micro world that I’ve created.” The other one that you have is a negative predictor associated with lower well-being in singlehood which is family pressure to a couple and marry. You come home for the holidays and Aunt Sally says, “Iris, you’re so great. Why are you single?”

This happened to me and a stranger said this to me.

It’s super annoying. Can you coach your family? Family is hard to get rid of. If you have a friend who’s not being supportive, that’s easier to manage than a parent or a sibling. Besides giving them Geoff’s paper to read, can you coach them to be more supportive of the choices that you’re making, even if they’re not the choices that they would make? How do you do this in between one person and the world with your team or your community?

You’re right in saying striving for a goal implies that the current situation is unsatisfactory. It’s not great or feeling good until you achieve that goal. Also, achieving a goal like when you do hit that New York Times bestseller position, you’ll be happy for maybe 5 days or maybe 5. It’s also a lot of effort for a relatively small payoff.

Thank you for the when, Iris.

No ifs, only whens. Talking about needs maybe more specifically, sometimes you can have certain feelings of lacking that you think will be solved by a partner. Maybe you feel a little bit alone or you would want to go to the zoo but nobody wants to come with you, “I wish I had a partner because then that would be solved.” That lacking is in your mind and solved potentially by a partner but when you think about what the need is, having somebody to do something with or having somebody who listens to my story, these needs can be met by other people as well in different constellations. They don’t all have to come together in one person.

When you recognize what the underlying need is, then you can satisfy that need in other equally satisfying ways. It’s a bit of a lack of imagination that we often suffer from because that’s what we’re told, “Partners solve your problems,” but when you think about it a bit longer, your friends, families or meetup groups can solve your problems or meet your needs.

I’m going to take the pressure off myself by essentially stealing Iris’s answer. For my frame on this, you’re pretty much right on the money. I would phrase it this way because you’re talking about getting in touch with your values but you’re also talking about what I’m about to say, which is getting in touch with your feelings. Be honest with yourself about what you’re feeling. One of the groups of people we haven’t actively documented but I’m sure exist are people who are happier being alone but don’t notice because everyone else is telling them to get into a relationship. It’s paying attention to what you feel, being prepared to be surprised by what you feel and being okay with feeling things that are not normative. All of those would be good skills.

In the case that you’re talking specifically about, everybody is going to feel a sense of lack or a sense of want at different times. Single people will have a particular flavor of these. Think about other people who can meet the needs that those feelings bring up. Also exercising the ability to sit with those feelings and sometimes figure out, “Is what I’m feeling something that I want a romantic partner to solve or if I sit here and let myself feel that for a little while and can handle it on my own, does that feeling dissipate a little bit?”

From an Attachment Theory point of view, what happens when we have an unmet need or an unmet craving is that should activate the attachment system and want us to go and seek somebody out. The better you can get itself soothing, you might find that you’re able to operate in a little bit more independent relationship space too. It’s developing those capacities to sit with your feelings, listen to what they’re telling you and not react to them too quickly. Sometimes they will tell you that you want a romantic partner.

In my field, a lot of the conversation is about the single people who are doing well but the single people who are not doing well are equally as valid in experience as the people who are thriving. If that’s you and after a lot of soul searching, you’re like, “I like the comfort and stability of having a romantic partner in the house with me,” then that’s great too. Being honest with how you feel about things and developing your skills to handle your feelings on your own is so empowering. Whether you want to be in a relationship or you don’t want, whether you want to have a business or a best seller, to me, it all starts from there.

That is wonderful. I agree. I validate this whole comment. In the end, what it’s all about is how are you a good adult. One way to be an adult is not to be impulsive with your feelings and try to satisfy them immediately. Get to know yourself and live an examined life.

To call back to an episode with my friend Sarah Stinson and Lawrence Williams, Sarah was talking about valuing yourself. She said, “Just because you’re hungry doesn’t mean you should eat a Hot Pockets. You should hold out for something healthier.” With that thought, Iris, I want to say thank you for joining us again.

I so enjoy the two sides of yourself that you bring to these episodes, the behavioral scientist, someone who has thought very deeply about humans and human connections about judgment choices and emotions and then the solo side of you, the opinionated and the unapologetic side of you, balancing that. Geoff, I’m thrilled to have you back. I appreciate your tolerance of us editorializing along the way. I’m deeply grateful for you and your team building this library of findings that are validating and are spurring conversations like this one. For both of you, thanks for such a great episode.

Thank you. I appreciate the opportunity to come and talk about this. This is a three-year passion project for us. We hope it delivers something good for single people.

Cheers.

Important Links

- Geoff MacDonald

- Iris Schneider

- Coping or Thriving Within A Person’s Perspective On Singlehood

- Bella DePaulo – Past episode

- Relationship Anarchy – Past episode

- Attachment Theory

- Sarah Stinson and Lawrence Williams – Past episode

- https://PubMed.NCBI.NLM.NIH.gov/36534959/

About Geoff MacDonald

About Iris Schneider